Why is there a UK housing shortage

How have government measures contributed to the UK housing shortage?

What factors are driving house prices in the UK and leaving property unaffordable for many?

- Ramping up of “Right to Buy” scheme and decrease in council housing stock

- 1988 Housing Act

- Failure to build houses

- Deregulaton of the UK's financial sector

- How UK house prices have risen and fallen

Homeownership was once commonplace in the UK, but now younger generations are struggling to get onto the housing ladder. According to the Office for National Statistics, a third of 35- to 44-year-olds in England were renting from a private landlord in 2017, compared with fewer than one in 10 in 1997. Now, renting has overtaken buying and since 2008, there have been more new private rented lettings a year than new sales.

In recent decades, the cost of housing has risen at a faster rate than wages, which has made it difficult for those who do not own their houses already to buy. The average house price in the UK is £216,750 and the average salary is £27,440, so houses are roughly eight times the average yearly salary. Different regions have more extreme differences though, in London the average house price is £484,716 which is 14 times the average salary of £34,320.

Measures have been brought in to help people buy to varying degrees of success. One of those measures has been to introduce low-deposit mortgages but then people have found that monthly mortgage repayments are unaffordable. To reduce the monthly mortgage repayment a larger deposit is needed, which is difficult to save up for whilst also renting. As a percentage of income, those renting privately in England spend 31.9% of their monthly wage on rent, vs 17.8% for owner-occupiers according to Statista.

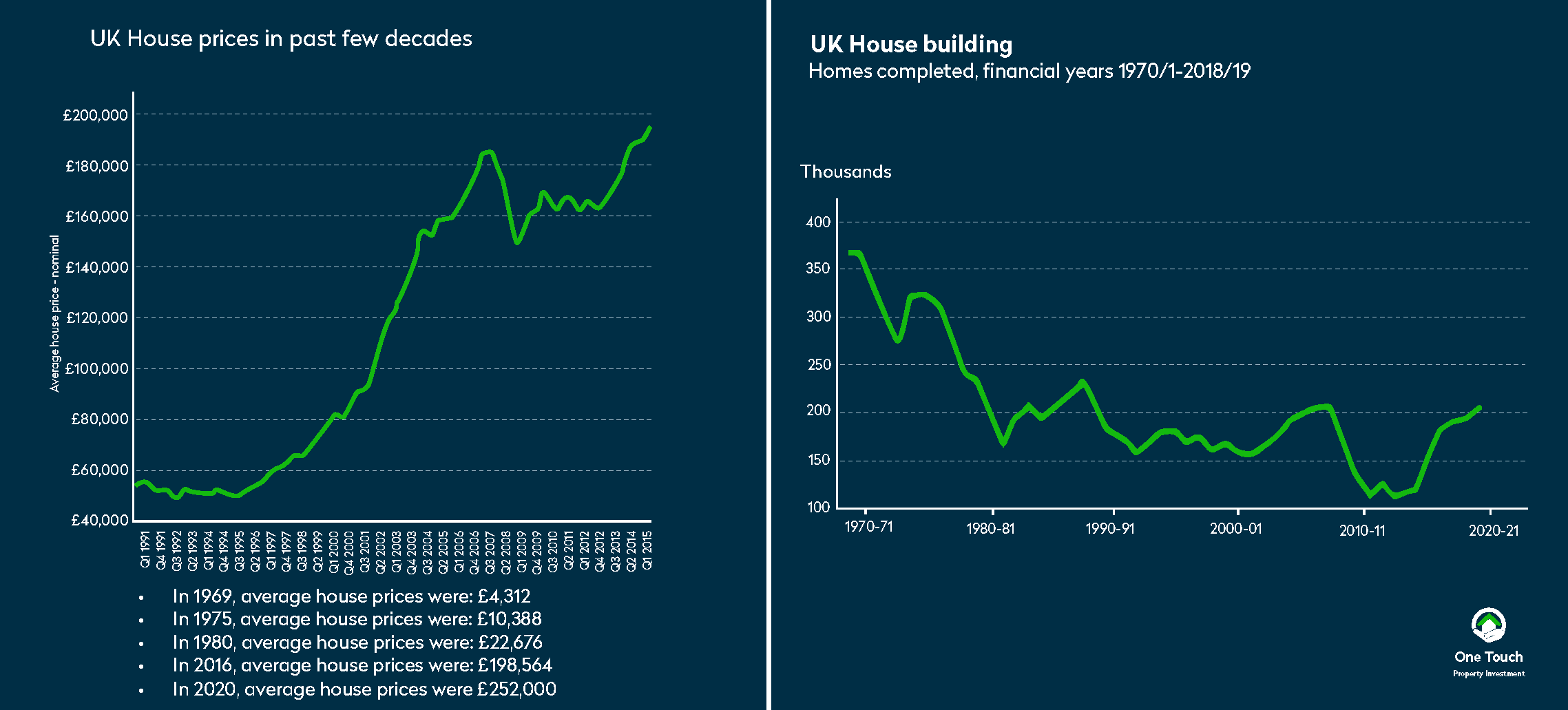

The housing market was not always so inaccessible. At the start of the 1970s the average house price was £4,057. Even if you chose not to own your own home and rented instead, almost a third of homes across Great Britain were affordable social housing provided by local authorities. The average annual salary was £1079, so the cost of a house was essentially less than four times average yearly income. By the end of 1970s though, the average house price had quadrupled to £19,925, and subsequent government policies have put more pressure on the housing market.

These are some of the government actions over recent decades that have contributed to the housing crisis we have today, and how house prices rose and fell abruptly due to financial crises and lenient lending criteria.

1980s – Ramping up of “Right to Buy” scheme and decrease in council housing stock

In 1980 Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government stepped up the “Right to Buy” scheme and made it central to her government policy, playing up to the British ideal of home ownership. The policy existed before the 80s and allowed council house tenants the opportunity to buy their home, but Thatcher introduced legislation to heavily discount existing stock through the Housing Act of 1980.

Consequently, this meant that local councils were unable to build new houses at the rate they were selling them because the amount of money recouped from sales did not cover the cost to build. This led to a massive imbalance of affordable housing vs. demand, and it is something that plagues the housing market to this day.

By 1985 almost half a million council houses had been sold in England alone under the right to buy scheme, and this led to a massive increase in homeownership. The effect of Right to Buy combined with the demolition of outdated stock meant that the number of council houses available for affordable rent had plummeted. In 1999 only 50 new houses were built by councils, and the ability for councils to build houses and access funds was limited by the 1988 Housing Act.

Overall, between 1977 and 2009 the proportion of people living in council houses in Great Britain decreased from 32% to 9%.

There is some hope that councils will start building more houses now, which will push up the proportion of people living in council housing. In 2018/19 Theresa May lifted the cap on how much councils can borrow to build houses. Before the pandemic, sixty councils had announced that they were planning on taking advantage of the cap being lifted, and some councils were expected to hit government house building targets.

1988 Housing Act

The 1988 Housing Act further restricted councils’ abilities to house their constituents. The act gave local authorities the power to source funding to build new houses and repair older ones from private companies. Councils could not get funding from private sources, so they were at a disadvantage compared to local authorities. This meant that many houses transferred from being under council control to local authorities. By 1997, 250,000 houses had been placed under the control of local authorities and this practice was continued under successive Labour governments.

Failure to build houses

It was not just councils who were unable to meet their targets for house building, but private stock has failed to keep up with demand as well. No recent government, either Labour who were in power from 1997 – 2010 or Conservative from 2020 onwards has ever built enough housing to keep up with demand.

In the 1950s, 60s and 70s, public sector housing led the way, and this was also a busy period for slum clearances. Between 1955 – 1980 67,000 homes a year were demolished or closed. Since that time, private house building has been the biggest contributor to stock due to constraints councils were facing. In 2010 house building figures reached their lowest figure since 1946 of 135,990 and has declined ever since. In 2013 the figure was 135,590, and the low completion rate of new homes has caused significant pressure on supply as the UK’s population had continued to grow.

The government has set itself a figure of building 300,000 new homes per year to keep up with demand. In 2019/20, 243,770 new homes were delivered. Whilst this is the highest number of new homes being built since 1987, it is still below the government’s own target it has set for itself. Furthermore, the Coronavirus pandemic had a significant impact on house building in 2020 – which saw the second-lowest rate of new build completions since 2012.

Deregulation of UK financial sector meant a wider mortgage availability

Thatcher’s government also began to deregulate parts of the financial sector, and this allowed mortgage lenders to relax mortgage application criteria and decide for themselves how much they should charge. This led to more people being able to get a mortgage, regardless of whether they had the means to repay it or not.

Even though people were going into negative equity in the 1990s, mortgage companies were still being relaxed in who could borrow, and as there were not enough homes being built, there was still a supply /demand imbalance. In 1992 179,100 new homes were built, which was just over half of what was being built 20 years previously.

By 1999 Northern Rock had launched a mortgage called “Together” which allowed homeowners to borrow up to 125% of the value of their home. Other types of mortgages and were coming onto the market as well, that many had expressed concerns over. For example, self-certification mortgages which allowed the self-employed to declare their own earnings without providing payslips as proof – in effect this allowed them the ability to borrow far more than they could pay back.

Another is the interest-only mortgage, where borrowers only paid off the interest on their mortgage and only had to pay back the amount they borrowed at the end of the term. This was considered risky at the time as the ability to repay at the end hinged on the value of the property going up.

In 2008 US firm Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy and the news had a domino effect across the globe, causing a global financial recession. Mortgage lenders began taking some products off the market and lending was curtailed. More stringent assessments combined with people losing their jobs and savings meant that fewer mortgage applications were approved.

The recession did create opportunity for some. The Bank of England cut interest rates to historically low levels to shield the mortgage markets from the effects of the recession. This meant that borrowing was cheaper than ever, so for those with savings, property looked like a good investment.

At the end of the banking crisis stricter lending criteria was put in place to restrict these kinds of mortgages. For example, it is now very difficult to get an interest-only mortgage unless you are borrowing on a buy-to-let property.

The deregulation, selling off affordable stock and failure to build has led to house prices rising sharply. This is mainly fueled by a supply / demand imbalance and the availability of cheap credit. It is important to note that although house prices have fluctuated in the short term due to recessions and stricter financial regulations, they have always been on an upward trajectory.

UK House Prices Rise and Fall

Due to the deregulation in the financial sector, mortgage companies relaxed their lending criteria. The sudden availability of new mortgage options allowed people who were once priced out of the property market access to it. This led to dramatic increases in house prices and homeownership, but with risks attached that have severely affected property prices over recent decades.

From 1983 house prices skyrocketed. However, that was all to come crashing down in the early 1990s. This led to many homeowners going into negative equity – where your mortgage is worth more than the house you borrowed on. Some homeowners handed the keys back to the bank, and some fell behind on their mortgage repayments. As there was a larger supply of available housing stock on the market, house prices were suppressed.

By 1993 the average house price was £54,121, and prices started to pick up again. Wages did not keep pace with rise in property prices though and the first signs appear of an imbalance between earnings and house prices. Over ten years mortgage repayments went up from around a fifth of take-home pay to around a third and it became more difficult to save for a sizable deposit that would keep mortgage repayments reasonable.

By 2007 the average house price had reached £185,196 but then the great recession hit in 2008 and house prices were immediately impacted due to unemployment and tighter lending criteria that had been introduced. In 2008 house prices fell to £176,853.

Over the decade between 2010 and 2020 house prices gradually began to climb again. Although the rise was not as acute in some areas compared to others. Regionally, London, the East of England, and the South East saw the largest rises of 62%, 48% and 43% respectively. Demand tends to be highest in these regions as they have the highest economic output due to job availability and earning potential.

Read our free buy-to-let guide to learn more about the sector!

The latest figures from 2020 suggest house prices rose by 8.5% to an average of £238,211, despite a pandemic. The rise can be in part attributed to the stamp duty holiday where the potential savings has given incentive to those thinking of buying, and pent-up demand due to a stall in the housing market during the spring lockdown. The property market shows no sign of slowing, with Good Move predicting a further 17% increase in average house prices over the decade to 2030.

Those looking to invest in UK property can be encouraged by the signs of continued growth in the market as the outlook in the long term looks positive. A shortage of available homes has buoyed prices and low interest rates make buy-to-let property attractive to investors as interest rates on borrowing are low.

The government’s failure to adequately address the housing shortage means there will be continued demand for existing stock and measures put in place to encourage home ownership such as help-to-buy are expected to do little to boost home ownership levels. The issue has existed for decades and since 2008 renting has overtaken buying, which means that property investors can expect good occupancy levels.

Start your property journey...

For those interested in learning more about the UK property market and latest investment opportunities, why not get in touch with one of our consultants today? Alternatively to learn more, why not read about the UK property market fundamentals or for those not based in the UK, how to access the UK property market from overseas.

Recommended Properties

Related Articles

Are you curious?

Speak with an experienced consultant who will help identify suitable properties that will capture the exciting fundamental mentioned here.

WANT TO LEARN MORE ABOUT PROPERTY INVESTMENT?

SIGN UP TO OUR NEWSLETTER NOW!